| Six name types

“The names of famous Samurai I know are just a part of their names.”

Believe it or not, this is true. The names of famous Samurai we know are only partially written in history books. One Samurai in particular is the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川 家康. His whole name is as follows:

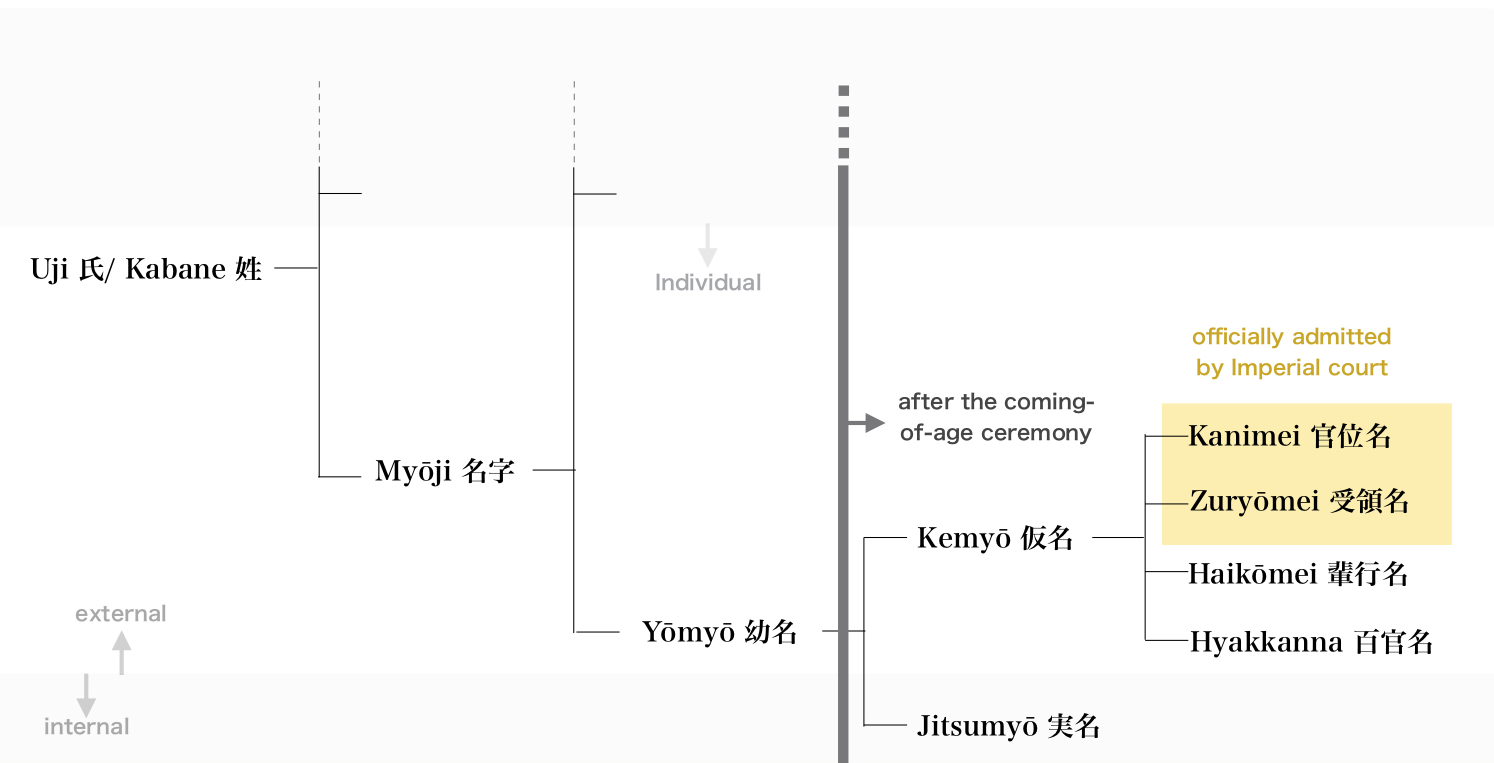

Samurai basically had these six name types:

Family name: Myōji 名字

Pseudonym: Kemyō 仮名 or Tsūshō 通称

Clan name: Uji 氏

Hereditary title: Kabane 姓

True name: Jitsumyō 実名 or Imina 諱

Childhood name: Yōmyō 幼名 or Warawana 童名

Here is the history and the meaning to the order of each name.

| In the beginning were Uji and Kabane

| In the beginning were Uji and Kabane

Uji was a social group based on blood relationships. They were roughly divided into two types; the one derived from the place name (Soga 蘇我, Fujiwara 藤原, Kibi 吉備, Koma 高麗, and Hata 秦), and one derived from the job title (Nakatomi 中臣, Ōtomo 大伴 and Mononobe 物部).

Kabane were hereditary titles used with Uji to denote rank and political standing, and for those officially admitted to the imperial court. At first there were more than thirty titles, but eventually they were consolidated into eight, identified singularly as: Yakusa no kabane 八色の姓. The second rank of the eight, Ason 朝臣 was the most popular Kabane given.

Later, as the Uji began to devolve into individual households, the Kabane gradually faded from use.

| As Samurai gained power, Myōji arose

| As Samurai gained power, Myōji arose

In the late Heian period (794–1185), paternalistic families became more independent, and as such lessened their ties to their wider Uji roots. These families often managed manors called Shōen 荘園; Gun 郡, Gō 郷, and Ho 保, and bestowed the place name on their family name Myōji 名字 in order to protest about land ownership [1]. That is why the majority of Samurai names are deeply connected with the place name.

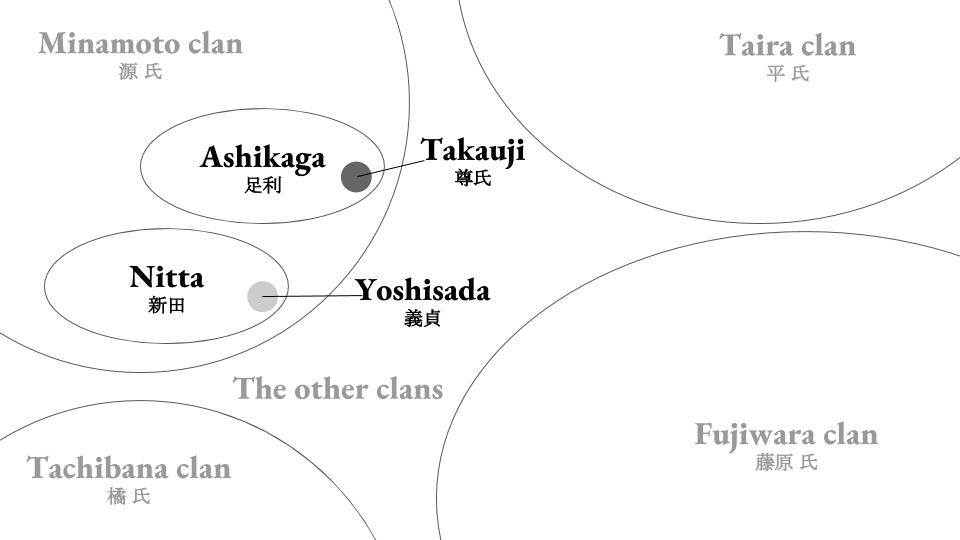

For example, a famous samurai in the late Kamakura period (1185–1333), Ashikaga Takauji 足利 尊氏 and his rival Nitta Yoshisada 新田 義貞 had different Myōji name, but their Uji name is the same, Minamoto 源.

There are other patterns of Myoji that do not stem from the land name. Examples include, a name taken from the local administration system like: Hongo 本郷 and, Jinbo 神保. Other examples are Tsukushi 筑紫 and Rusu 留守 [2], taken from government posts.

[1] 大藤修, 日本人の姓・苗字・名前, p27

[2] 大藤修, 日本人の姓・苗字・名前, p36-41

| A child Yōmyō, An adult Jitsumyō

| A child Yōmyō, An adult Jitsumyō

Yōmyō 幼名 or Warawana 童名 is the childhood name before having the coming-of-age ceremony, Genpuku 元服. Additionally, there are suffixes added to the final portion of the name such as Maru 丸, Chiyo 千代, Matsu 松, Yasya 夜叉, Hōshi 法師, etc.

Maru 丸 means a chamberpot, to expel the devils by stench

Chiyo 千代 means a thousand years

Matsu 松 means pine tree representing long prosperity

Yasya 夜叉 means the high spirit

Hōshi 法師 means monk, being under the protection of Buddha

Jitsumyō 実名 or Imina 諱 is one’s private name, created by themselves, or bestowed at the coming-of-age ceremony. Imina is also described as Imina 忌み名 (directly translated as “the name to avoid” [3]), because it was believed that if someone other than the owner were to know this name, it would give power to that second person – ultimately allowing them to control the person. Imina is thus maintained as a secret to not only guarantee an egregious usage of the name, but to also maintain one’s individual politeness [4].

Samurai publicly called themselves in order from to Myōji and Kemyō. (see below) They paid attention to Imina and changed it casually.

The custom called Henki 偏諱 came about when a lord wished to give one of his kanji characters to one of his retainers (someone attached to a household) as a reward, or urged the changing of an Imina [4]. A samurai changed his Imina over 15 times [5]. Changing the names was normal among the Samurai rank.

[3] 穂積 陳重,穂積 重行, 忌み名の研究, p151-152

[4] 水野 智之, 名前と権力の中世史 室町将軍の朝廷戦略, p5-7

[5] 立花宗茂, 改名欄

| Kemyō, pseudonym, a wide variety

| Kemyō, pseudonym, a wide variety

Kemyō is the external name used in place of Imina. They are roughly divided into 4 types:

Kanimei 官位名

Zuryōmei 受領名

Hyakkanna 百官名

Haikōmei 輩行名

Kanimei 官位名

An official rank given when admitted by the Imperial court. The ranks were limited, meaning that they were given to a small number of influential Samurai. For example, Daijō-daijin 太政大臣 of Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣 秀吉 and Dainagon 大納言 of Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康.

Zuryōmei 受領名

An unofficial rank given without the authorization of the Imperial court. Daimyōs 大名, the powerful feudal lords during the Sengoku period, gave their vassals Zuryōmei as a reward.

e.g. Kazusa-no-suke 上総介 (the governor of Kazusa province) / Kaga-no-kami 加賀守 (the governor of Kaga province)

Hyakkanna 百官名

Refers to an official-rank-style name that Samurai called to announce oneself, such a name was often boomed out publicly among the Samurai society. “Sakon 左近” of Shima Sakon 島 左近 is a famous example.

e.g. Zaemon 左衛門 / Uemon 右兵衛 / Jibu 治部 / Mondo 主水

Haikōmei 輩行名

It represents the seniority in the “Haikō” (birth order) in names such as Tarō 太郎 (meaning, one’s first son), Jirō 次郎 (meaning, one’s second son) and Saburō 三郎 (meaning, one’s third son). The order is sometimes changed from one’s mother’s rank.

| Names and natures do often agree

| Names and natures do often agree

There is an old saying that 名は体を表す (Na wa tai wo arawasu), meaning “names and natures do often agree.”

Samurai traditionally had several names like above, and changed their name to fit different situations and life stages. They strove to be true their name, trained diligently in the martial arts, and adopted an appreciation and dedication toward all manner of learning. For a samurai, learning was always done with the very greatest degree of care.

As such, one’s name was the crystal of their principle and consistently served to navigate them to even greater heights.

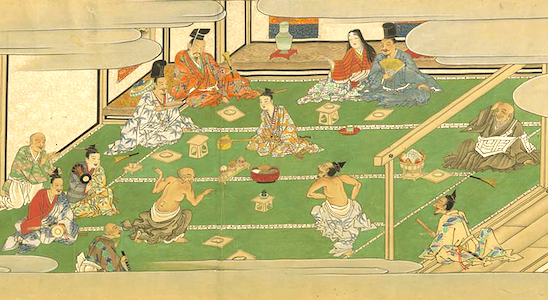

Each relationship is represented in the following graph.